When incorporating best practices and guidelines for HIV care, clinicians must take into account their clients’ mental health and substance use needs. Approximately 30- 50% of people living with HIV/AIDS have current or past severe to moderate depression. At its highest estimate, that’s more than double the prevalence of the general population.

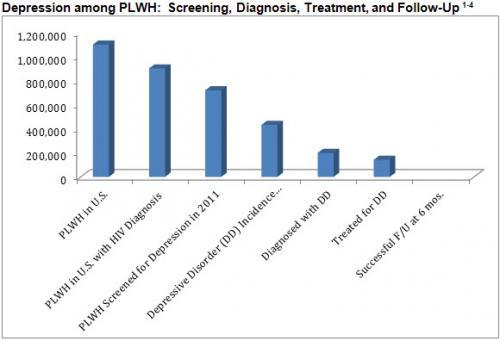

Based on HRSA HIVQUAL measures obtained in Ryan White-funded programs, we see that not all clients with HIV are being screened for depression. Of those screened and diagnosed with a depressive disorder, only a small percentage was actually treated for their depression. It should be noted that these numbers look only at depression and do not take into account other mental health issues clients with HIV/AIDS face.

To address the gaps between screening, diagnosis, referral, and treatment of mental health and substance use disorders, a panel of multidisciplinary mental health experts from several AETCs was convened by the AETC National Resource Center; this group developed the Integrating Mental Health and Substance Use Care into HIV Primary Care Toolkit. The toolkit is designed to assist organizations to assess their readiness to provide needed behavioral health services and contains a repository of resources to assist in roll-out of these services.

Why should medical providers be focusing on identifying and treating mental health and substance use issues?

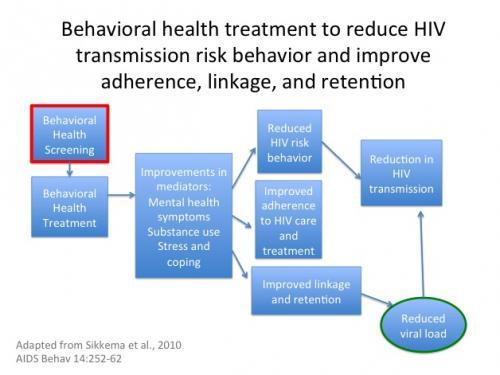

Mental health and physical health are inseparable. HIV and mental health/substance use comorbidities can greatly affect a client’s treatment outcome, so it is imperative that medical providers intervene in some capacity to increase treatment adherence and improve their clients’ quality of life. For clients who are HIV-positive, a co-occurring depression increases the likelihood of morbidity and mortality, non-initiation of antiretroviral treatment (ART), non-adherence to ART once initiated, slower virologic suppression, and increased sexual risk behavior. We find similar outcomes for clients with comorbid substance use issues (e.g. poor ART adherence, increased mortality). From a public health standpoint, primary care of people living with HIV/AIDS should include monitoring of substance abuse and mental health, since it is often associated with risk behaviors that can lead to further transmission of HIV.

When clients with HIV/AIDS are receiving mental health treatment, we see improved HIV treatment adherence resulting in better CD4 cell counts and viral load suppression.5,6 One study reports that people who are HIV+ receiving antidepressant treatment are four times more likely to accept ART and twice as likely to achieve viral suppression.7 Clinical settings with HIV/AIDS patients require a workforce capable of addressing the complex mental health needs of their patients. Because mental health is directly related to health outcomes, incorporation of state-of-the-science mental health care screening(s), diagnosis, treatment, and maintenance in HIV primary care is essential for best practice in HIV care.

How can the AETC improve treatment outcomes for people living with HIV/AIDS and comorbid mental health/substance use diagnoses?

As an AETC and center for mental health training, our role in integrating these services is indirect but tangible. Training is necessary to build capacity, and has shown to be effective in increasing providers’ intention to change their practice. Surveying over 10,000 primary care providers who attended HIV training between 7/1/2011 and 6/30/2013, we found that 6,072 (57%) reported practice change intentions following training. Specifically, they identified three types of practice change: create/revise protocols/policies (49%); create/revise procedures in practice (53%); change the clinical management of their patients (51%). Of those who were not planning practice change, 90% of 4,626 providers indicated that training validated their current practice. These sort of “booster” trainings will be needed to maintain changes in practice. Integration of mental health into primary care does not work without support and consultation for primary care clinicians.

There is no single approach to integrating mental health care into HIV care. Each clinic environment (“culture”) is different. Also keep in mind that approaches need to be individualized for different patient populations. Training providers to use the “Integrating Mental Health and Substance Use Care into HIV Primary Care Toolkit” through tailored training, technical assistance, and clinical support and consultation activities, the AETC can meet the clinic’s needs and provide the support necessary to bring about practice change that enhances care integration.

References

- HIV/AIDS Care Continuum

- Steven M Asch, MD, MPH, Amy M Kilbourne, PhD, MPH, Allen L Gifford, MD, M Audrey Burnam, PhD, Barbara Turner, MD, MSEd, Martin F Shapiro, MD, PhD, Samuel A Bozzette, MD, PhD, and for the HCSUS Consortium. Underdiagnosis of Depression in HIV - Who Are We Missing? J Gen Intern Med. Jun 2003; 18(6): 450–460.doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20938.x

- “Clients Who Received Risk, Mental Health and Substance Abuse Screenings in United States, 2011.”

- VA Primary Care Manual: Depression

- Cook JA, Grey D, Burke-Miller J, Cohen MH, Anastos K, Ghandi M, et al. Effects of treated and untreated depressive symptoms on highly active antiretroviral therapy use in a US multi-site cohort of HIV-positive women. AIDS Care. 2006;18:93–100.

- Horberg MA, Silverberg MJ, Hurley LB, Towner WJ, Klein DB, Bersoff-Matcha S, …Kovach DA. Effects of depression and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use on adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy and on clinical outcomes in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008 Mar 1;47(3):384-90.

- Tsai AC, Weiser SD, Petersen ML, Ragland K, Kushel MB, Bangsberg DR. A marginal structural model to estimate the causal effect of antidepressant medication treatment on viral suppression among homeless and marginally housed persons with HIV. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(12):1282–1290.